“To do two things at once

is to do neither.”

—Publilius Syrus

If doing the most important thing is the most important thing, why would you try to do anything else at the same time?

“Multitaskers were just lousy at everything.” Multitasking is a lie.

It’s a lie because nearly everyone accepts it as an effective thing to do. It’s become so mainstream that people actually think it’s something they should do, and do as often as possible. We not only hear talk about doing it, we even hear talk about getting better at it.

Multitasking is neither efficient nor effective. In the world of results, it will fail you every time.

“Multitasking is merely the opportunity to screw up more than one thing at a time.”

—Steve Uzzell

When you try to do two things at once, you either can’t or won’t do either well.

“Multitasking is merely the opportunity to screw up more than one thing at a time.”

MONKEY MIND

People are trying to do too many things at once and forget to do something they should do.

We think we can, so we think we should. Kids studying while texting, listening to music, or watching television. Adults driving while talking on the phone, eating, applying makeup, or even shaving. Doing something in one room while talking to someone in the next. Smartphones in hands before napkins hit laps.

It’s not that we have too little time to do all the things we need to do, it’s that we feel the need to do too many things in the time we have. So we double and triple up in the hope of getting everything done.

Billy Collins summed it up well: “We call it multitasking, which makes it sound like an ability to do lots of things at the same time. ... A Buddhist would call this monkey mind.” We think we’re mastering multitasking, but we’re just driving ourselves bananas.

JUGGLING IS AN ILLUSION

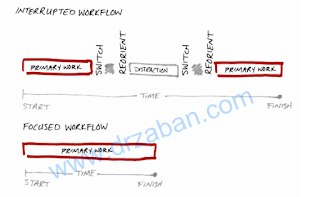

When you switch from one task to another, voluntarily or not, two things happen. The first is nearly instantaneous: you decide to switch. The second is less predictable: you have to activate the “rules” for whatever you’re about to do.

Switching between two simple tasks like watching television and folding clothes is quick and relatively painless. However, if you’re working on a spreadsheet and a co-worker pops into your office to discuss a business problem, the relative complexity of those tasks makes it impossible to easily jump back and forth. It always takes some time to start a new task and restart the one you quit, and there’s no guarantee that you’ll ever pick up exactly where you left off. There is a price for this. “The cost in terms of extra time from having to task switch depends on how complex or simple the tasks are, ” reports researcher Dr. David Meyer. “It can range from time increases of 25 percent or less for simple tasks to well over 100 percent or more for very complicated tasks.” Task switching exacts a cost few realize they’re even paying.

—Publilius Syrus

If doing the most important thing is the most important thing, why would you try to do anything else at the same time?

“Multitaskers were just lousy at everything.” Multitasking is a lie.

It’s a lie because nearly everyone accepts it as an effective thing to do. It’s become so mainstream that people actually think it’s something they should do, and do as often as possible. We not only hear talk about doing it, we even hear talk about getting better at it.

Multitasking is neither efficient nor effective. In the world of results, it will fail you every time.

“Multitasking is merely the opportunity to screw up more than one thing at a time.”

—Steve Uzzell

When you try to do two things at once, you either can’t or won’t do either well.

“Multitasking is merely the opportunity to screw up more than one thing at a time.”

MONKEY MIND

People are trying to do too many things at once and forget to do something they should do.

We think we can, so we think we should. Kids studying while texting, listening to music, or watching television. Adults driving while talking on the phone, eating, applying makeup, or even shaving. Doing something in one room while talking to someone in the next. Smartphones in hands before napkins hit laps.

It’s not that we have too little time to do all the things we need to do, it’s that we feel the need to do too many things in the time we have. So we double and triple up in the hope of getting everything done.

Billy Collins summed it up well: “We call it multitasking, which makes it sound like an ability to do lots of things at the same time. ... A Buddhist would call this monkey mind.” We think we’re mastering multitasking, but we’re just driving ourselves bananas.

JUGGLING IS AN ILLUSION

When you switch from one task to another, voluntarily or not, two things happen. The first is nearly instantaneous: you decide to switch. The second is less predictable: you have to activate the “rules” for whatever you’re about to do.

Switching between two simple tasks like watching television and folding clothes is quick and relatively painless. However, if you’re working on a spreadsheet and a co-worker pops into your office to discuss a business problem, the relative complexity of those tasks makes it impossible to easily jump back and forth. It always takes some time to start a new task and restart the one you quit, and there’s no guarantee that you’ll ever pick up exactly where you left off. There is a price for this. “The cost in terms of extra time from having to task switch depends on how complex or simple the tasks are, ” reports researcher Dr. David Meyer. “It can range from time increases of 25 percent or less for simple tasks to well over 100 percent or more for very complicated tasks.” Task switching exacts a cost few realize they’re even paying.

Multitasking doesn’t save time —it wastes time.

BRAIN CHANNELS

You can do two things

at once, but you can’t focus effectively on two things at once.

You can actually give attention to two things, but that is

what’s called “divided attention.” And make no mistake. Take on

two things and your attention gets divided. Take on a third and

something gets dropped.

The problem of trying to focus on two things at once shows

up when one task demands more attention or if it crosses into a

channel already in use. When your spouse is describing the way

the living room furniture has been rearranged, you engage your

visual cortex to see it in your mind’s eye. If you happen to be

driving at that moment, this channel interference means you are

now seeing the new sofa and love seat combination and are

effectively blind to the car braking in front of you. You simply

can’t effectively focus on two important things at the same time.

Every time we try to do two or more things at once, we’re

simply dividing up our focus and dumbing down all of the

outcomes in the process. Here’s the short list of how multitasking

short-circuits us:

1. There is just so much brain capability at any one time. Divide

it up as much as you want, but you’ll pay a price in time and

effectiveness.

2. The more time you spend switched to another task, the less

likely you are to get back to your original task. This is how

loose ends pile up.

3. Bounce between one activity and another and you lose time as

your brain reorients to the new task. Those milliseconds add

up. Researchers estimate we lose 28 percent of an average

workday to multitasking ineffectiveness.

4. Chronic multitaskers develop a distorted sense of how long it

takes to do things. They almost always believe tasks take

longer to complete than is actually required.

5. Multitaskers make more mistakes than non-multitaskers. They

often make poorer decisions because they favor new

information over old, even if the older information is more

valuable.

6. Multitaskers experience more life-reducing, happiness squelching stress.

Knowing how multitasking leads to mistakes, poor choices, and

stress we attempt it anyway Maybe it’s just too tempting.

Multitasking slows us down and makes us slower

witted.

DRIVEN TO DISTRACTION

BIG IDEAS

1. Distraction is natural. Don’t feel bad when you get

distracted. Everyone gets distracted.

2. Multitasking takes a toll. At home or at work, distractions

lead to poor choices, painful mistakes, and unnecessary stress.

3. Distraction undermines results. When you try to do too much

at once, you can end up doing nothing well. Figure out what

matters most in the moment and give it your undivided

attention.

In order to be able to put the principle of The ONE Thing to

work, you can’t buy into the lie that trying to do two things at once

is a good idea. Though multitasking is sometimes possible, it’s

never possible to do it effectively.

Comments

Post a Comment