“The truth is, balance is

bunk. It is an unattainable

pipe dream... . The quest

for balance between work

and life, as we've come to

think of it, isn’t just a

losing proposition; it’

s a

hurtful, destructive one.”

—Keith H. Hammonds

Nothing ever achieves absolute balance. Nothing. No matter how imperceptible it might be, what appears to be a state of balance is something entirely different— an act of balancing.

A “balanced life” is a myth—a misleading concept most accept as a worthy and attainable goal without ever stopping to truly consider it. I want you to consider it. I want you to challenge it. I want you to reject it.

A balanced life is a lie.

The idea of balance is exactly that—an idea. In philosophy “the golden mean” is the moderate middle between polar extremes, a concept used to describe a place between two positions that is more desirable than one state or the other. This is a grand idea, but not a very practical one. Idealistic, but not realistic. Balance doesn’t exist.

We hear about balance so much we automatically assume it’s exactly what we should be seeking. It’s not. Purpose, meaning, significance—these are what make a successful life. Seek them and you will most certainly live your life out of balance, criss-crossing an invisible middle line as you pursue your priorities. The act of living a full life by giving time to what matters is a balancing act. Extraordinary results require focused attention and time. Time on one thing means time away from another. This makes balance impossible.

THE GENESIS OF A MYTH

Historically, balancing our lives is a novel privilege to even consider. For thousands of years, work was life. If you didn’t work—hunt game, harvest crops, or raise livestock—you didn’t live long. But things changed. Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer Prizewinning Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Pates of Human Societies illustrates how farm-based societies that generated a surplus of food ultimately gave rise to professional specialization. “Twelve thousand years ago, everybody on earth was a hunter-gatherer; now almost all of us are farmers or else are fed by farmers.” This freedom from having to forage or farm allowed people to become scholars and craftsmen. Some worked to put food on our tables while others built the tables. At first, most people worked according to their needs and ambitions. The blacksmith didn’t have to stay at the forge until 5 p.m.; he could go home when the horse’s feet were shod. Then 19th-century industrialization saw for the first time large numbers working for someone else. The story became one of hard-driving bosses, year-round work schedules, and lighted factories that ignored dawn and dusk. Consequently, the 20th century witnessed the start of significant grassroots movements to protect workers and limit work hours. Still, the term “work-life balance” wasn’t coined until the mid-1980s when more than half of all married women joined the workforce. To paraphrase Ralph E. Gomory’s preface in the 2005 book Being Together, Working Apart: Dual-Career Families and the Work-Life Balance, we went from a family unit with a breadwinner and a homemaker to one with two breadwinners and no homemaker. Anyone with a pulse knows who got stuck with the extra work in the beginning. However, by the ’90s “work-life balance” had quickly become a common watchword for men too. A LexisNexis survey of the top 100 newspapers and magazines around the world shows a dramatic rise in the number of articles on the topic, from 32 in the decade from 1986 to 1996 to a high of 1,674 articles in 2007 alone (see figure 9). It’s probably not a coincidence that the ramp-up of technology parallels the rise in the belief that something is missing in our lives. Infiltrated space and fewer boundaries will do that. Rooted in real-life challenges, the idea of “work-life balance” has clearly captured our minds and imagination.

The reason we shouldn’t pursue balance is that the magic never happens in the middle; magic happens at the extremes. The dilemma is that chasing the extremes presents real challenges. We naturally understand that success lies at the outer edges, but we don’t know how to manage our lives while we’re out there.

—Keith H. Hammonds

Nothing ever achieves absolute balance. Nothing. No matter how imperceptible it might be, what appears to be a state of balance is something entirely different— an act of balancing.

A “balanced life” is a myth—a misleading concept most accept as a worthy and attainable goal without ever stopping to truly consider it. I want you to consider it. I want you to challenge it. I want you to reject it.

A balanced life is a lie.

The idea of balance is exactly that—an idea. In philosophy “the golden mean” is the moderate middle between polar extremes, a concept used to describe a place between two positions that is more desirable than one state or the other. This is a grand idea, but not a very practical one. Idealistic, but not realistic. Balance doesn’t exist.

We hear about balance so much we automatically assume it’s exactly what we should be seeking. It’s not. Purpose, meaning, significance—these are what make a successful life. Seek them and you will most certainly live your life out of balance, criss-crossing an invisible middle line as you pursue your priorities. The act of living a full life by giving time to what matters is a balancing act. Extraordinary results require focused attention and time. Time on one thing means time away from another. This makes balance impossible.

THE GENESIS OF A MYTH

Historically, balancing our lives is a novel privilege to even consider. For thousands of years, work was life. If you didn’t work—hunt game, harvest crops, or raise livestock—you didn’t live long. But things changed. Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer Prizewinning Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Pates of Human Societies illustrates how farm-based societies that generated a surplus of food ultimately gave rise to professional specialization. “Twelve thousand years ago, everybody on earth was a hunter-gatherer; now almost all of us are farmers or else are fed by farmers.” This freedom from having to forage or farm allowed people to become scholars and craftsmen. Some worked to put food on our tables while others built the tables. At first, most people worked according to their needs and ambitions. The blacksmith didn’t have to stay at the forge until 5 p.m.; he could go home when the horse’s feet were shod. Then 19th-century industrialization saw for the first time large numbers working for someone else. The story became one of hard-driving bosses, year-round work schedules, and lighted factories that ignored dawn and dusk. Consequently, the 20th century witnessed the start of significant grassroots movements to protect workers and limit work hours. Still, the term “work-life balance” wasn’t coined until the mid-1980s when more than half of all married women joined the workforce. To paraphrase Ralph E. Gomory’s preface in the 2005 book Being Together, Working Apart: Dual-Career Families and the Work-Life Balance, we went from a family unit with a breadwinner and a homemaker to one with two breadwinners and no homemaker. Anyone with a pulse knows who got stuck with the extra work in the beginning. However, by the ’90s “work-life balance” had quickly become a common watchword for men too. A LexisNexis survey of the top 100 newspapers and magazines around the world shows a dramatic rise in the number of articles on the topic, from 32 in the decade from 1986 to 1996 to a high of 1,674 articles in 2007 alone (see figure 9). It’s probably not a coincidence that the ramp-up of technology parallels the rise in the belief that something is missing in our lives. Infiltrated space and fewer boundaries will do that. Rooted in real-life challenges, the idea of “work-life balance” has clearly captured our minds and imagination.

The number of times “work-life balance” is mentioned in

newspaper and magazine articles has exploded in recent years.

MIDDLE MISMANAGEMENT

The desire for balance makes sense. Enough time for everything

and everything done in time. It sounds so appealing that just thinking about it makes us feel serene and peaceful. This calm is

so real that we just know it’s the way life was meant to be. But it’s

not.

If you think of balance as the middle, then out of balance is

when you’re away from it. Get too far away from the middle and

you’re living at the extremes. The problem with living in the

middle is that it prevents you from making extraordinary time

commitments to anything. In your effort to attend to all things,

everything gets shortchanged and nothing gets its due. Sometimes

this can be okay and sometimes not. Knowing when to pursue the

middle and when to pursue the extremes is in essence the true

beginning of wisdom. Extraordinary results are achieved by this

negotiation with your time.

Pursuing a balanced life means never pursuing anything at

the extremes.

The reason we shouldn’t pursue balance is that the magic never happens in the middle; magic happens at the extremes. The dilemma is that chasing the extremes presents real challenges. We naturally understand that success lies at the outer edges, but we don’t know how to manage our lives while we’re out there.

Pursuing the extremes presents its own set of problems.

Just like playing to the middle, playing to the extremes is the kind of middle mismanagement that plays out all the time.

TIME WAITS FOR NO ONE

Time waits for no one. Push something to an extreme and

postponement can become permanent.

When you gamble with your time, you may be placing a bet

you can’t cover. Even if you’re sure you can win, be careful that

you can live with what you lose.

Toying with time will lead you down a rabbit hole with no

way out. Believing this lie does its harm by convincing you to do

things you shouldn’t and stop doing things you should. Middle mismanagement can be one of the most destructive things you ever

do. You can’t ignore the inevitability of time.

So if achieving balance is a lie, then what do you do?

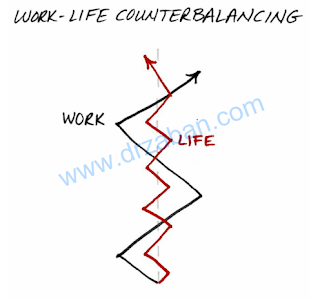

Counterbalance. Replace the word “balance” with “counterbalance” and what

you experience makes sense. The things we presume to have

balance are really just counterbalancing.

COUNTERBALANCING—THE LONG AND SHORT

OF IT

Leaving some things undone is a necessary trade-off for extraordinary results. But you can’t leave everything undone, and

that’s where counterbalancing comes in. The idea of

counterbalancing is that you never go so far that you can’t find

your way back or stay so long that there is nothing waiting for you

when you return.

This is so important that your very life may hang in the

balance. An 11-year study of nearly 7,100 British civil servants

concluded that habitual long hours can be deadly. Researchers

showed that individuals who worked more than 11 hours a day (a

55-plus hour workweek) were 67 percent more likely to suffer

from heart disease. Counterbalancing is not only about your sense

of well-being, it’s essential to your being well.

Extraordinary results at work require longer periods between

counterbalancing.

There are two types of counterbalancing: the balancing

between work and personal life and the balancing within each. In

the world of professional success, it’s not about how much

overtime you put in; the key ingredient is focused time over time.

To achieve an extraordinary result you must choose what matters

most and give it all the time it demands. This requires getting

extremely out of balance in relation to all other work issues, with

only infrequent counterbalancing to address them. In your

personal world, awareness is the essential ingredient. Awareness of

your spirit and body, awareness of your family and friends,

awareness of your personal needs—none of these can be sacrificed

if you intend to “have a life,

” so you can never forsake them for

work or one for the other. You can move back and forth quickly

between these and often even combine the activities around them,

but you can’t neglect any of them for long. Your personal life

requires tight counterbalancing.

Whether or not to go out of balance isn’t really the question.

The question is: “Do you go short or long?” In your personal life,

go short and avoid long periods where you’re out of balance.

Going short lets you stay connected to all the things that matter

most and move them along together. In your professional life, go

long and make peace with the idea that the pursuit of extraordinary

results may require you to be out of balance for long periods. Going long allows you to focus on what matters most, even at the

expense of other, lesser priorities. In your personal life, nothing

gets left behind. At work it’s required.

LIFE IS A BALANCING ACT

When you

change your language from balancing to prioritizing, you see your

choices more clearly and open the door to changing your destiny.

Extraordinary results demand that you set a priority and act on it.

When you act on your priority, you’ll automatically go out of

balance, giving more time to one thing over another. The challenge

then doesn’t become one of not going out of balance, for in fact

you must. The challenge becomes how long you stay on your

priority. To be able to address your priorities outside of work, be clear about your most important work priority so you can get it

done. Then go home and be clear about your priorities there so

you can get back to work.

When you’re supposed to be working, work, and when

you’re supposed to be playing, play. It’s a weird tightrope you’re

walking, but it’s only when you get your priorities mixed up that

things fall apart.

BIG IDEAS

1. Think about two balancing buckets. Separate

your work life and personal life into two distinct buckets—not

to compartmentalize them, just for counterbalancing. Each has

its own counterbalancing goals and approaches.

2. Counterbalance your work bucket. View work as involving a

skill or knowledge that must be mastered. This will cause you

to give disproportionate time to your ONE Thing and will

throw the rest of your work day, week, month, and year

continually out of balance. Your work life is divided into two

distinct areas—what matters most and everything else. You

will have to take what matters to the extremes and be okay

with what happens to the rest. Professional success requires it.

3. Counterbalance your personal life bucket. Acknowledge

that your life actually has multiple areas and that each requires a minimum of attention for you to feel that you “have a life.”

Drop any one and you will feel the effects. This requires

constant awareness. You must never go too long or too far

without counterbalancing them so that they are all active areas

of your life. Your personal life requires it.

Start leading a counterbalanced life. Let the right things take

precedence when they should and get to the rest when you can.

An extraordinary life is a counterbalancing act

Comments

Post a Comment